Jam Sessions – Where Bebop was Born

Musicians generally work in the evenings. This was no different in the 1930’s and 40’s. Swing musicians of the era would start work in clubs and ballrooms in the evening when people would go out for some after-work entertainment. But when audiences left the clubs and went home to bed, the Swing musicians instead went to jam sessions. The most famous of these was Minton’s Playhouse, which opened in New York City in 1940. It is said that this is where Bebop was born. The house band at Milton’s included drummer Kenny Clarke and pianist Thelonious Monk. And the musicians that jammed there included Jazz greats like Ben Webster, Charlie Christian, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, and Charlie Parker.

These jam sessions were for serious musicians and involved a lot of experimentation. And it quickly became quite competitive. Musicians would test each other’s abilities by intentionally making the songs difficult to play. They would pick a standard song like ‘I Got Rhythm’, but play it incredibly fast, using complex chord substitutions, and transpose the song up one semitone after every repeat. This would very quickly root out any amateur musicians. In fact, when Charlie Parker attended his first few jam sessions, he couldn’t keep up and completely stuffed up his soloing and was kicked out of the jam session for being incompetent. This humiliation inspired him to go home and practice 15 hours a day. These jam sessions are where Bebop was developed and perfected.

The Gradual Revolution

Many people speak of bebop as a ‘revolution’ in Jazz. One that completely broke with the past. This isn’t true. Bebop grew organically out of Swing, and shares many of its elements and features. As we just saw, Bebop developed naturally in jam sessions. One of the reasons people believe Bebop was a break with the past is due to an accident of history. Bebop developed in the early 1940’s, with the first recordings of Bebop appearing in late 1944 and early 1945. Unfortunately, there was a musician’s strike which prevented all unionised musicians from recording albums between 1942 and 1944 in the US. Consequently, there are no recordings of early bebop as it was first developing. So by the time Bebop was heard for the first time on record, it had already developed and grown for 2 years.

Numerous elements of bebop could be found in Swing including:

- Art Tatum used complex harmonies and chord substitutions

- Count Basie had began comping with the piano rather than playing stride

- Coleman Hawkins improvised vertically over the song Body & Soul, outlining the chord progression but adding in chromatic harmonies

- Duke Ellington was a master at using dissonant chord voicings

Bebop took all of these elements to the extreme. Before Bebop, if you wanted to improvise, you could get away with knowing little music theory and largely just feeling your way through the song – using your ear to find what sounded good. With the arrival of Bebop, feeling was not enough – you had to know and understand.

Below is a quick comparison between Swing music and Bebop.

| Element | Swing (1930-45) | Bebop (1945-50) |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Dance music | Art/Listening Music |

| Drums | Bass drum on beat | Ride cymbal on beat |

| Piano | Stride Piano Chords | Comping Shell (Bud Powell) voicings Right hand soloing |

| Guitar | On the beat strumming | Single lines with electric guitar |

| Bass | Walking bassline | Walking bassline |

| Size & | Big Band | Small group |

| Focus | Focus on overall feel or groove | Focus on individual virtuosity |

| Solos | Arpeggiate 7th Chords Warm, lyrical Largely diatonic | Arpeggiate Available Tensions Superimposition Vibratoless Use of exotic scales Largely 8th note runs Start phrases off the beat |

| Harmony | Simple Harmony - 7th chords with natural tensions Largely diatonic with lot of ii-V-I’s | Complex Harmony - ♭5, ♭9, altered dominants, tritone substitutions) Much more chromatic |

| Rhythm | Even and predictable Mix of short and long duration | Complex & quasi-unpredictable accents Short note duration notes |

| Melody | Use of repetition Lyrical & smooth Clearly outlining chords Regular, symmetrical, with some syncopation Easy to sing | Limited melodic cues and repetition Improvisational Phrases Complex, angular, irregular, asymmetrical, serpentine Predictable melodic contour Harmonic outline less obvious Difficult to sing |

| Composition | Largely arranged | Largely improvised |

| Tempo | Slow to medium | Fast paced with lots of notes |

| Rhythm section | Keeps the beat & plays the chords | Interactive |

Bebop Lines

The classic Bebop line generally follows the following formula:

-

- Start on an off-beat;

- Arpeggiate the relevant chord up to an available tension – often a 9th (this can be preceded by a note a semitone away from your first chord tone);

- Use a diatonic scale to down inserting chromatic passing notes (this is known as a Bebop scale);

- Use swung eighth notes but insert accents throughout the phrase to create a rhythmic element to your melody line (accenting some on and some off-beats);

- End the phrase with a downward movement (this is where the name ‘Bebop’ comes from – as the sounds ‘bee’ and ‘bop’ could be used to scat these melodic lines).

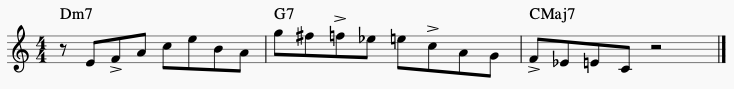

Below is an example of a typical Bebop line. Notice is starts on an off-beat, a semitone away from a chord tone, the arpeggiates up the chord (Dm7) from the 3rd to the 11th before returning back down via a scale with passing notes.

Of course, you will find descending arpeggios and ascending scale runs, but as a generalisation this is pretty accurate.

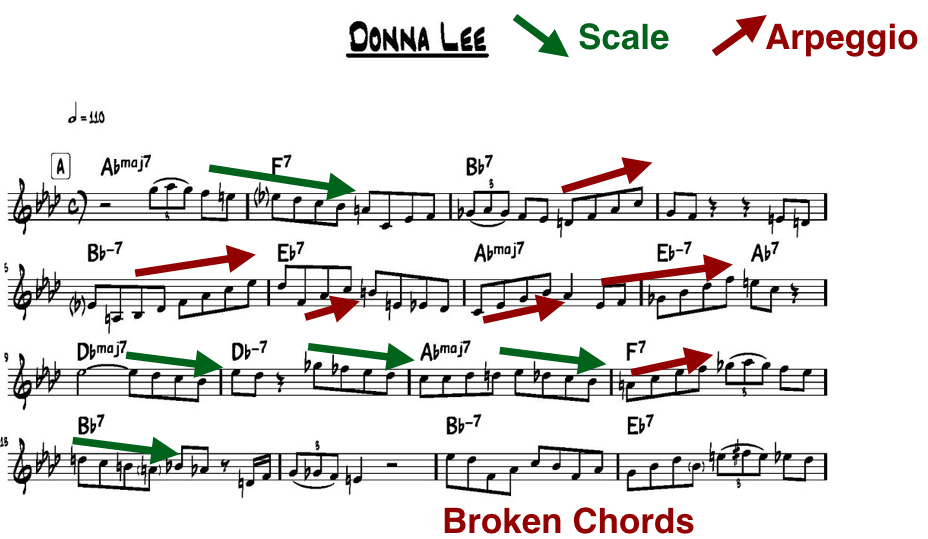

A good example of everything we have covered so far is the standard Donna Lee.

Have a Listen to

- Charlie Parker (alto sax)

- Dizzy Gillespie (trumpet)

- Bud Powell (piano)

- Thelonious Monk (piano/composer)

- Max Roach (drums)

- Dexter Gordon (tenor sax)

- J.J. Johnson (trombone)